The narrative around girls’ education across the world is one that is often framed by stories of barriers, resilience, progress and breakthroughs. These stories are relevant because they reveal both the scale of the challenge and the possibility of change. The stories of barriers often highlight the barriers that girls face in getting an education. For millions of girls globally, their education journey is shaped less by potential and more by circumstance. Poverty forces families to make impossible choices, and when resources are limited, girls are often the first to be withdrawn from school. Early marriage and adolescent pregnancy also interrupt schooling, leaving young women with little or no opportunity to return to school. Then there’s the barrier caused by violence and unsafe school environments, which forces girls to choose between staying at home or face the risk of attending classes.

Moreso, in situations where girls are enrolled in school, overcrowded classrooms, poorly resourced schools, and unqualified teachers often make learning feel irrelevant or discouraging, forcing them to lose interest before they are able to complete their education. These barriers are persistent and structural, but they are not insurmountable.

Alongside these challenges are powerful stories of progress, resilience and breakthroughs, where girls go on to overcome the barriers stacked against them, and nations have found ways to support them. Around the world, countries that have invested deliberately in girls’ education have shown that change is possible. Financial support programmes, safe learning environments, mentorship, and strong community engagement have improved retention and learning outcomes. In Rwanda, teenage mothers are supported to return to school through enabling policies and mentorship networks. In Kenya, initiatives that promote safe schooling, such as providing sanitary towels to help girls during menstruation and implementing school re-entry guidelines for those who drop out due to pregnancy, have created protective learning environments for girls. Across South Asia and Latin America, conditional cash transfers and scholarships have helped families keep girls in school, breaking cycles of poverty and dependence.

The barriers highlight the persistent barriers girls face, and the breakthroughs showcase the solutions, resilience, and possibilities that emerge when communities, governments, and organisations invest in girls’ education.

Nigeria faces its own set of intersecting obstacles. The United Nations Children Fund (UNICEF) reports that 7.6 million girls are out of school in Nigeria, with 3.9 million at the primary and 3.7 million at the junior secondary level. These numbers reflect the effect of structural and societal barriers that keep girls out of school. Poverty continues to limit access, with families often prioritising boys’ education when school fees, uniforms, and transportation costs are high. Early marriage and adolescent pregnancy pull girls out of classrooms, particularly in northern states, and many never get a second chance. Insecurity, including kidnapping threats and unsafe school routes, further discourages attendance. Social and cultural norms sometimes reinforce domestic responsibilities or early marriage as a priority over schooling. Together, these factors have positioned Nigeria as one of the countries with the highest number of out-of-school girls globally.

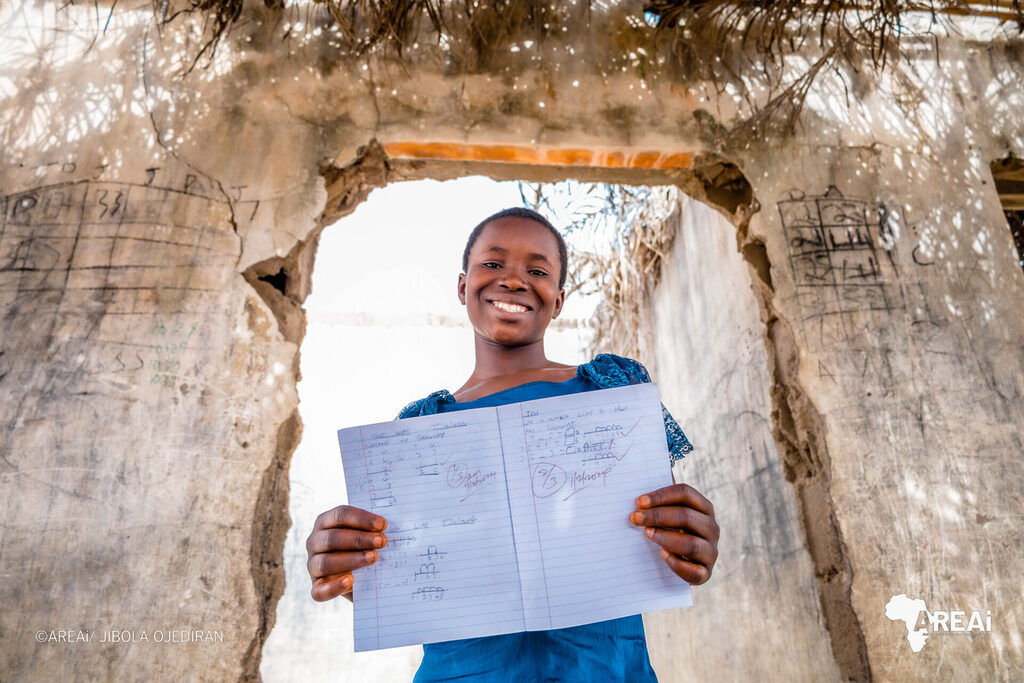

Yet, within this reality, Nigeria also offers its own story of progress, one that holds important lessons for government action. AREAi’s Getting Girls Equal (GGE) programme provides a compelling case study of how targeted, gender-responsive interventions can drive meaningful change in girls’ education outcomes.

The GGE programme was designed to address not just access to education, but the conditions that determine whether girls stay in school and succeed. Through a combination of grassroots action and system-focused interventions, the programme supported 30 schools to adopt gender-responsive teaching practices and inclusive school environments. These efforts transformed classrooms into safer spaces where girls were encouraged to participate, express themselves, and engage actively in learning. As a result, schools recorded significant improvements in girls’ classroom participation and academic engagement.

Central to this success was the programme’s investment in teachers and school leadership. A total of 60 teachers and 30 school administrators in Oyo state were trained in Gender-Responsive Pedagogy, equipping them to recognise and challenge bias, promote equitable learning, and model gender-transformative leadership. Rather than treating gender equality as an add-on, the programme embedded it into everyday teaching practice and school management.

Beyond the classroom, the GGE programme strengthened girls’ leadership and agency through initiatives such as the GGInspired Clubs and other peer-led platforms. More than 3,000 adolescent girls received mentorship, life skills training, and opportunities to build confidence and voice. These platforms enabled girls to articulate their needs, influence school culture, and lead peer engagement efforts, reinforcing their sense of belonging and purpose within the school system.

Equally important was the programme’s focus on community mobilisation and parental engagement. Parents and community leaders were engaged to challenge harmful gender norms and reaffirm the value of girls’ education through roundtable dialogues and sensitisation sessions. These conversations helped reduce resistance to girls staying in school and strengthened partnerships between schools and communities, an essential factor for sustainability.

The evidence from the Getting Girls Equal programme reveals that when educational interventions address social norms, school environments, teacher capacity, and girls’ leadership together, retention and learning outcomes improve. These are not isolated project successes; they are system-level lessons that can inform national policy and practice.

For the Nigerian government, the implications are significant. The GGE programme demonstrates that gender-responsive pedagogy should be embedded into pre-service and in-service teacher training nationwide. School-level gender policies and accountability mechanisms must become standard practice, not pilot initiatives. Community engagement should be recognised as a core component of education planning, particularly in regions where social norms strongly influence girls’ schooling. Safe, inclusive school environments must be prioritised alongside access and enrollment targets.

Most importantly, girls themselves must be seen as active stakeholders in education reform, not passive beneficiaries. Programmes that build girls’ leadership, confidence, and agency are essential to sustaining participation and achievement.

As Nigeria works toward achieving its national education goals and its commitments under SDG 4 and SDG 5, the question is no longer whether solutions exist. They do. The real question is whether these proven approaches will be scaled, funded, and institutionalised. The Getting Girls Equal programme offers a practical, evidence-based roadmap for how government action can improve and support girls’ education.

Written by: Elizabeth Abikoye

Director of Communications, Digital Media and Advocacy, AREAI